The Duality of Persons and Groups

Recall that in the one-mode case, multiplying the adjacency matrix times its transpose yields the common neighbors matrix \(\mathbf{M}\):

\[ \mathbf{M} = \mathbf{A}\mathbf{A}^T \]

As famously noted by Breiger (1974), doing the same for the affiliation matrix of a two-mode network also returns the common-neighbors matrix, but because objects in one mode can only connect to objects in another mode, this also reveals the duality of persons and groups: The connections between people are made up of the groups they share, and the connections between groups are revealed by the groups they share.

Thus, computing the common neighbors matrix for both persons and groups (also called the projection of the two-mode network into each of its modes) produces a one-mode similarity matrix between people and groups, where the similarities are defined by the number of objects in the other mode that they share.

For the people the relevant projection is:

\[ \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{A}\mathbf{A}^T \tag{1}\]

And for the groups:

\[ \mathbf{G} = \mathbf{A}^T\mathbf{A} \tag{2}\]

Let’s see how this works out with real data by loading our usual friend the Southern Women data:

In this case, equations Equation 2 and Equation 1 yield:

Evelyn Laura Theresa Brenda Charlotte Frances Eleanor Pearl Ruth

Evelyn 8 6 7 6 3 4 3 3 3

Laura 6 7 6 6 3 4 4 2 3

Theresa 7 6 8 6 4 4 4 3 4

Brenda 6 6 6 7 4 4 4 2 3

Charlotte 3 3 4 4 4 2 2 0 2

Frances 4 4 4 4 2 4 3 2 2

Eleanor 3 4 4 4 2 3 4 2 3

Pearl 3 2 3 2 0 2 2 3 2

Ruth 3 3 4 3 2 2 3 2 4

Verne 2 2 3 2 1 1 2 2 3

Myrna 2 1 2 1 0 1 1 2 2

Katherine 2 1 2 1 0 1 1 2 2

Sylvia 2 2 3 2 1 1 2 2 3

Nora 2 2 3 2 1 1 2 2 2

Helen 1 2 2 2 1 1 2 1 2

Dorothy 2 1 2 1 0 1 1 2 2

Olivia 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1

Flora 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1

Verne Myrna Katherine Sylvia Nora Helen Dorothy Olivia Flora

Evelyn 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 1

Laura 2 1 1 2 2 2 1 0 0

Theresa 3 2 2 3 3 2 2 1 1

Brenda 2 1 1 2 2 2 1 0 0

Charlotte 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

Frances 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0

Eleanor 2 1 1 2 2 2 1 0 0

Pearl 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 1

Ruth 3 2 2 3 2 2 2 1 1

Verne 4 3 3 4 3 3 2 1 1

Myrna 3 4 4 4 3 3 2 1 1

Katherine 3 4 6 6 5 3 2 1 1

Sylvia 4 4 6 7 6 4 2 1 1

Nora 3 3 5 6 8 4 1 2 2

Helen 3 3 3 4 4 5 1 1 1

Dorothy 2 2 2 2 1 1 2 1 1

Olivia 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2

Flora 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 2 6/27 3/2 4/12 9/26 2/25 5/19 3/15 9/16 4/8 6/10 2/23 4/7 11/21 8/3

6/27 3 2 3 2 3 3 2 3 1 0 0 0 0 0

3/2 2 3 3 2 3 3 2 3 2 0 0 0 0 0

4/12 3 3 6 4 6 5 4 5 2 0 0 0 0 0

9/26 2 2 4 4 4 3 3 3 2 0 0 0 0 0

2/25 3 3 6 4 8 6 6 7 3 0 0 0 0 0

5/19 3 3 5 3 6 8 5 7 4 1 1 1 1 1

3/15 2 2 4 3 6 5 10 8 5 3 2 4 2 2

9/16 3 3 5 3 7 7 8 14 9 4 1 5 2 2

4/8 1 2 2 2 3 4 5 9 12 4 3 5 3 3

6/10 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 4 4 5 2 5 3 3

2/23 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 1 3 2 4 2 1 1

4/7 0 0 0 0 0 1 4 5 5 5 2 6 3 3

11/21 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 2 3 3 1 3 3 3

8/3 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 2 3 3 1 3 3 3The off-diagonal entries of these square person by person (group by group) matrices is the number of groups (people) shared by each person (group) and the diagonals are the number of memberships of each person (the size of each group/event).

In igraph the relevant function is called bipartite_projection. It takes a bipartite graph as an input and returns a list containing igraph graph objects of both projections by default:

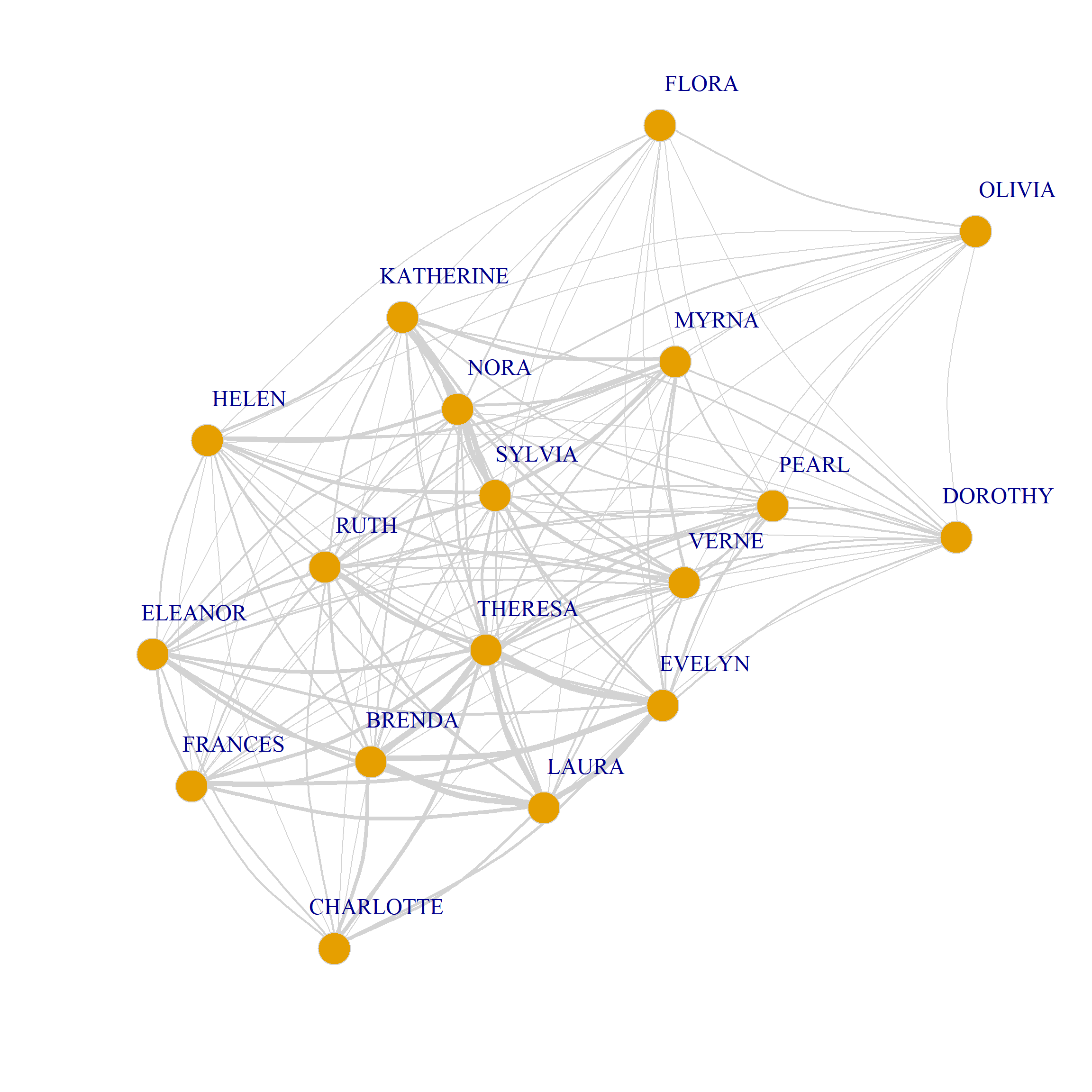

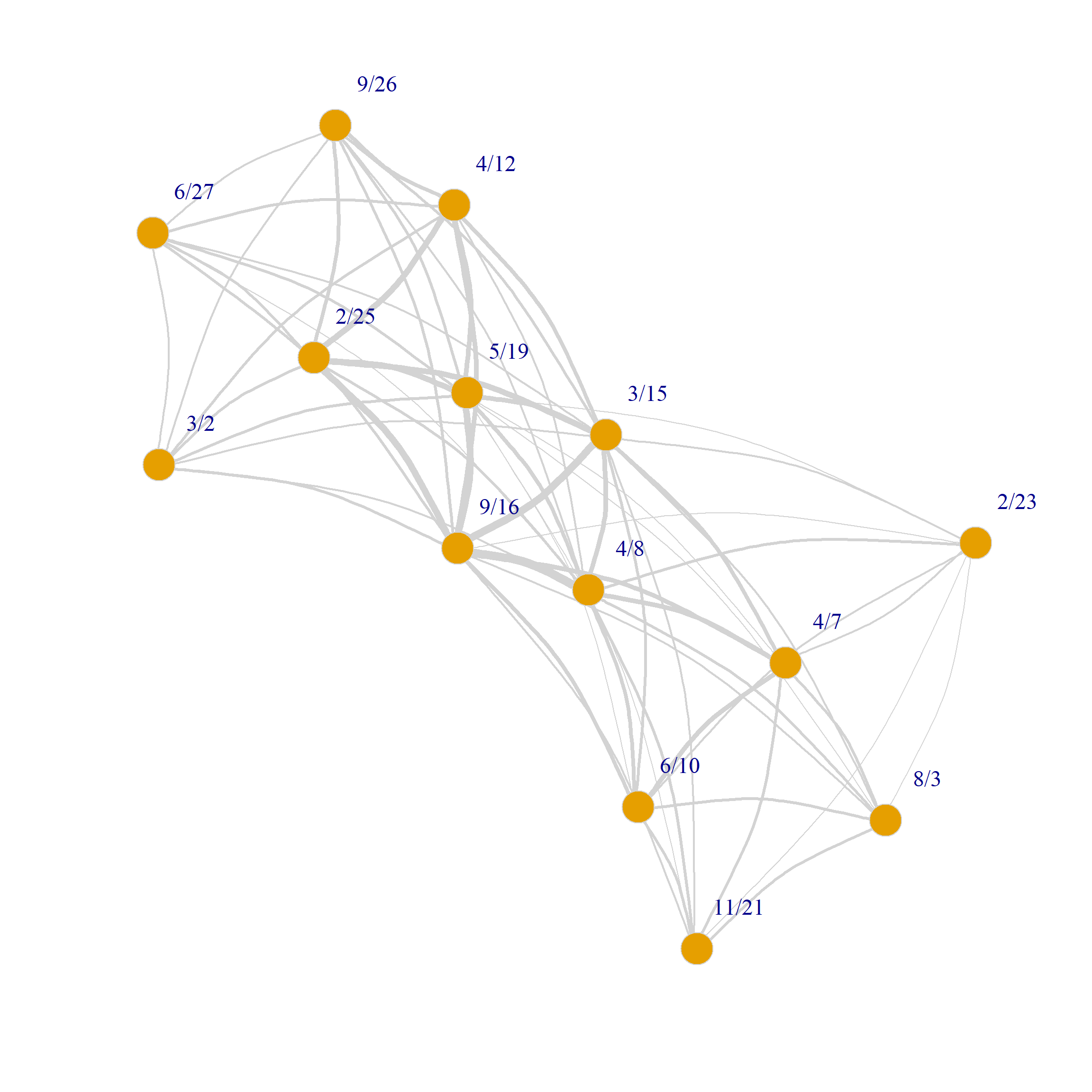

In the graph objects produced by the bipartite_projection function, the actual shared memberships and shared members are stored as an attribute of each edge called weight used in the plotting code for Figure 1 to set the edge.width:

$weight

[1] 6 6 7 3 4 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 1 6 6 3 4 4 3 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 6 4 4 4 4 3

[38] 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 1 1 4 4 4 3 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 3 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1

[75] 1 3 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 1 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 4 3 3 3 3 2 1 1

[112] 4 4 3 2 3 1 1 6 3 2 5 1 1 6 4 2 1 1 4 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 2$weight

[1] 2 3 2 3 3 3 1 2 3 2 3 3 3 2 2 4 6 5 5 2 4 4 3 3 2 3 6 7 3 6 7 4 5 1 1 1 1 1

[39] 8 5 4 3 2 2 2 9 5 4 2 2 1 5 4 3 3 3 5 3 3 2 2 1 1 3 3 3So to get the weighted projection matrix, we need to type:

Evelyn Laura Theresa Brenda Charlotte Frances Eleanor Pearl Ruth

Evelyn 0 6 7 6 3 4 3 3 3

Laura 6 0 6 6 3 4 4 2 3

Theresa 7 6 0 6 4 4 4 3 4

Brenda 6 6 6 0 4 4 4 2 3

Charlotte 3 3 4 4 0 2 2 0 2

Frances 4 4 4 4 2 0 3 2 2

Eleanor 3 4 4 4 2 3 0 2 3

Pearl 3 2 3 2 0 2 2 0 2

Ruth 3 3 4 3 2 2 3 2 0

Verne 2 2 3 2 1 1 2 2 3

Myrna 2 1 2 1 0 1 1 2 2

Katherine 2 1 2 1 0 1 1 2 2

Sylvia 2 2 3 2 1 1 2 2 3

Nora 2 2 3 2 1 1 2 2 2

Helen 1 2 2 2 1 1 2 1 2

Dorothy 2 1 2 1 0 1 1 2 2

Olivia 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1

Flora 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1

Verne Myrna Katherine Sylvia Nora Helen Dorothy Olivia Flora

Evelyn 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 1

Laura 2 1 1 2 2 2 1 0 0

Theresa 3 2 2 3 3 2 2 1 1

Brenda 2 1 1 2 2 2 1 0 0

Charlotte 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

Frances 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0

Eleanor 2 1 1 2 2 2 1 0 0

Pearl 2 2 2 2 2 1 2 1 1

Ruth 3 2 2 3 2 2 2 1 1

Verne 0 3 3 4 3 3 2 1 1

Myrna 3 0 4 4 3 3 2 1 1

Katherine 3 4 0 6 5 3 2 1 1

Sylvia 4 4 6 0 6 4 2 1 1

Nora 3 3 5 6 0 4 1 2 2

Helen 3 3 3 4 4 0 1 1 1

Dorothy 2 2 2 2 1 1 0 1 1

Olivia 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 0 2

Flora 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 0 6/27 3/2 4/12 9/26 2/25 5/19 3/15 9/16 4/8 6/10 2/23 4/7 11/21 8/3

6/27 0 2 3 2 3 3 2 3 1 0 0 0 0 0

3/2 2 0 3 2 3 3 2 3 2 0 0 0 0 0

4/12 3 3 0 4 6 5 4 5 2 0 0 0 0 0

9/26 2 2 4 0 4 3 3 3 2 0 0 0 0 0

2/25 3 3 6 4 0 6 6 7 3 0 0 0 0 0

5/19 3 3 5 3 6 0 5 7 4 1 1 1 1 1

3/15 2 2 4 3 6 5 0 8 5 3 2 4 2 2

9/16 3 3 5 3 7 7 8 0 9 4 1 5 2 2

4/8 1 2 2 2 3 4 5 9 0 4 3 5 3 3

6/10 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 4 4 0 2 5 3 3

2/23 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 1 3 2 0 2 1 1

4/7 0 0 0 0 0 1 4 5 5 5 2 0 3 3

11/21 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 2 3 3 1 3 0 3

8/3 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 2 3 3 1 3 3 0We can also use the weights to draw a weighted graph network plot of people and group projections. All we have to do is set the edge.with argument to the value of the edge weight attribute in the corresponding graph:

set.seed(123)

plot(G.p,

vertex.size=8, vertex.frame.color="lightgray",

vertex.label.dist=2, edge.curved=0.2,

vertex.label.cex = 1.5, edge.color = "lightgray",

edge.width = E(G.p)$weight)

set.seed(123)

plot(G.g,

vertex.size=8, vertex.frame.color="lightgray",

vertex.label.dist=2, edge.curved=0.2,

vertex.label.cex = 1.5, edge.color = "lightgray",

edge.width = E(G.g)$weight)

Note that because both G.p and G.g are weighted graphs we can calculate the weighted version of degree for both persons and groups from them (sometimes called the vertex strength).

In igraph we can do this using the strength function, which takes a weighted graph object as input:

Evelyn Laura Theresa Brenda Charlotte Frances Eleanor Pearl

50 45 57 46 24 32 36 31

Ruth Verne Myrna Katherine Sylvia Nora Helen Dorothy

40 38 33 37 46 43 34 24

Olivia Flora

14 14 6/27 3/2 4/12 9/26 2/25 5/19 3/15 9/16 4/8 6/10 2/23 4/7 11/21

19 20 32 23 38 41 48 59 46 25 13 28 18

8/3

18 Interestingly, as noted by Faust (1997, 167), there is a (dual!) mathematical connection between the strength of each vertex in the weighted projection and the centrality of the nodes from the other set they are connected to:

For people, the vertex strength is equal to the sum of the sizes of the groups they belong to minus their own degree.

For groups, the vertex strength is equal to the sum of the memberships of the people that belong to them, minus their own size.

We can verify this relationship for Evelyn:

sum.size.evelyn <- sum(A["Evelyn", ] * degree(g)[which(V(g)$type == TRUE)]) #sum of the sizes of the groups Evelyn belongs to

sum.size.evelyn - degree(g)[which(V(g)$name == "Evelyn")]Evelyn

50 Which is indeed Evelyn’s vertex strength.

Dually, the same relation applies to groups:

sum.mem.6.27 <- sum(A[, "6/27"] * degree(g)[which(V(g)$type == FALSE)]) #sum of the memberships of people in the first group

sum.mem.6.27 - degree(g)[which(V(g)$name == "6/27")]6/27

19 Which is indeed the vertex strength of the event held on 6/27.

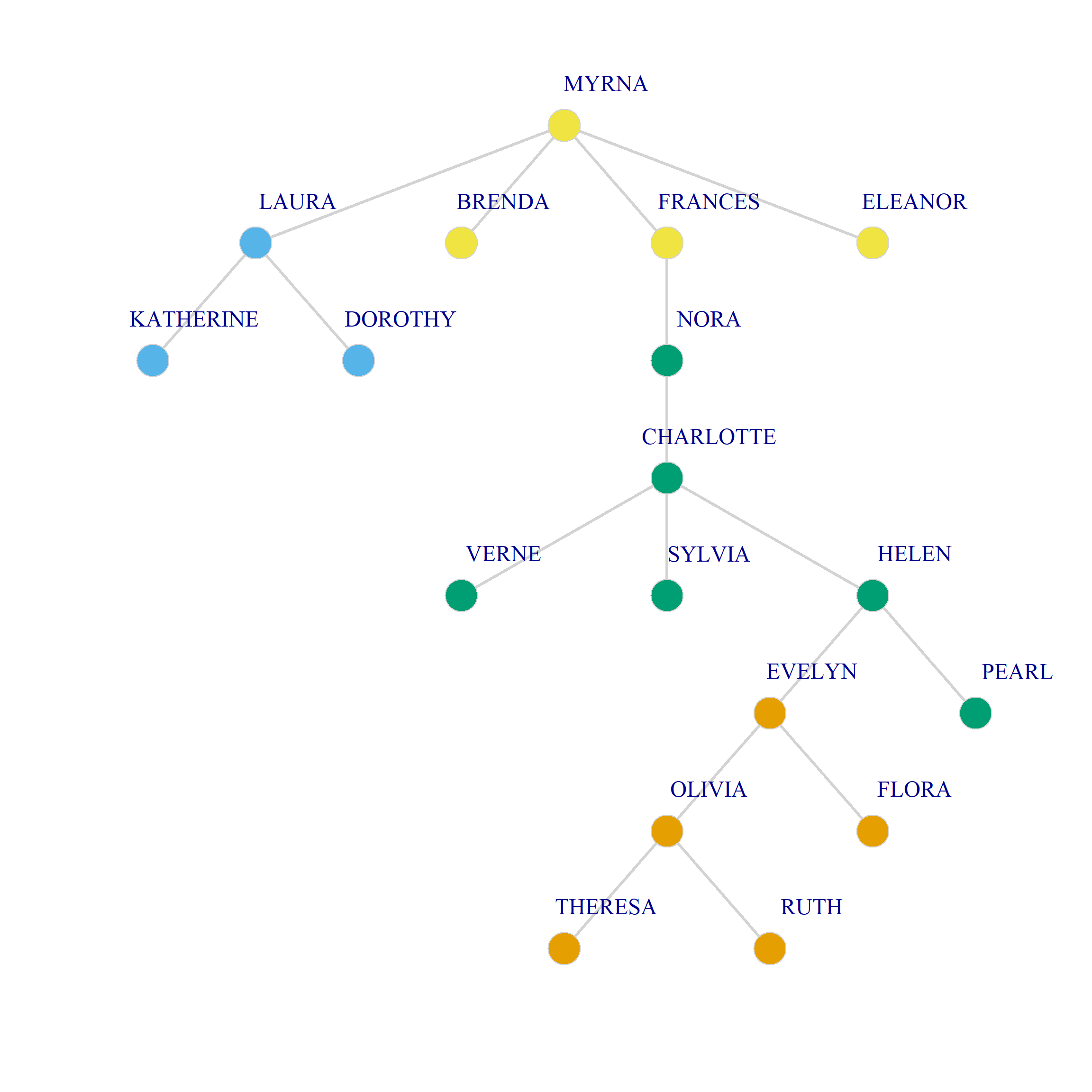

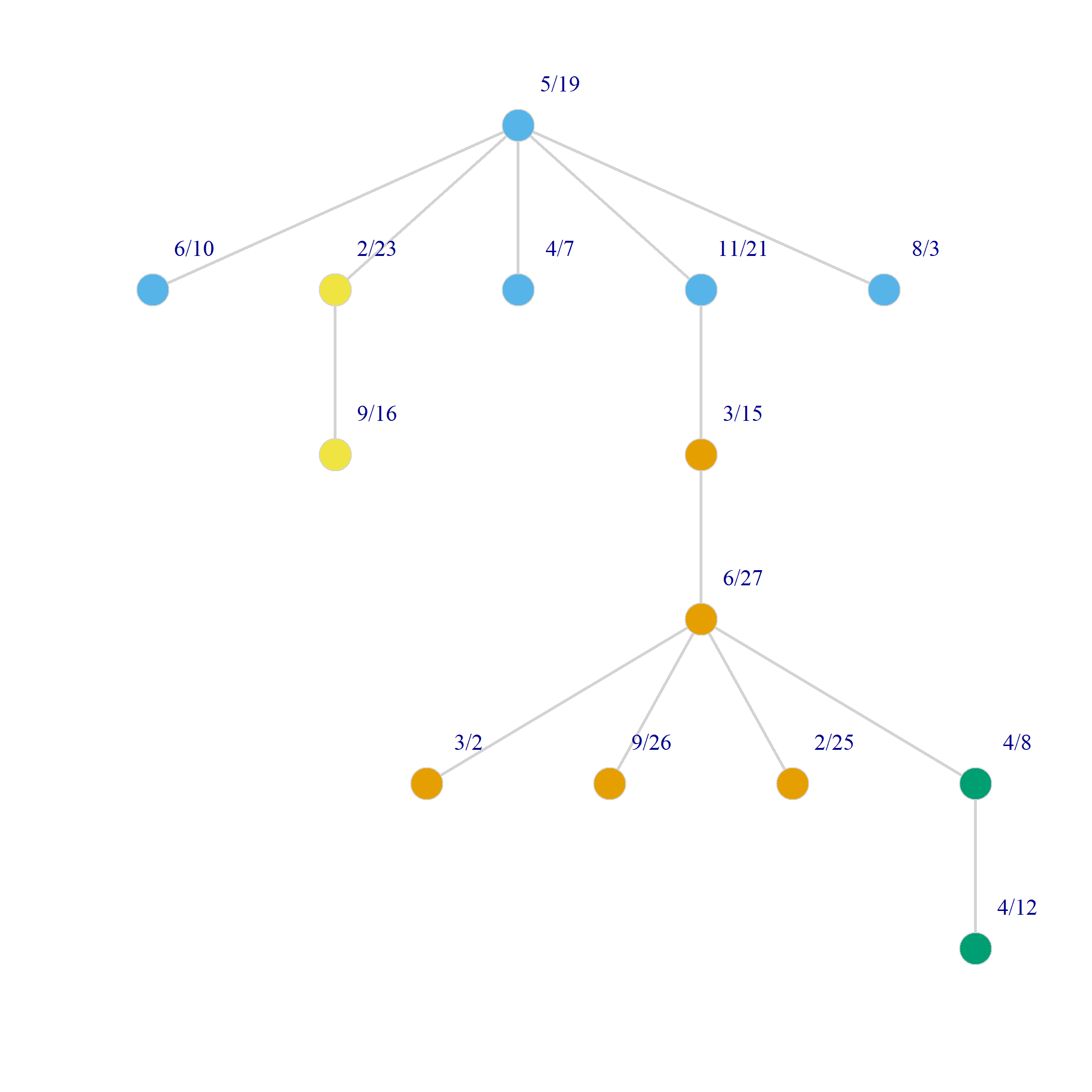

Visualizing Dual Projections Using the Minimum Spanning Tree

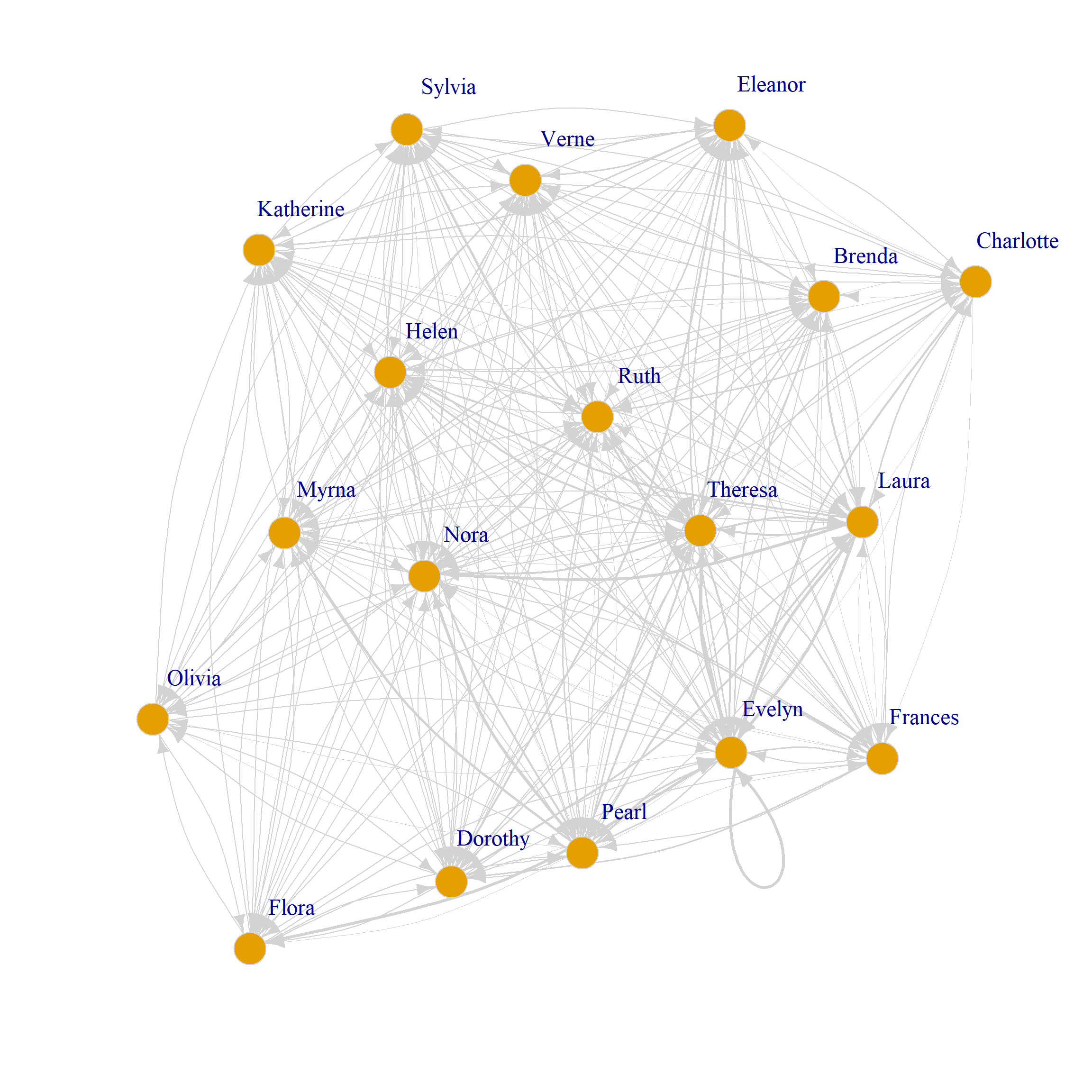

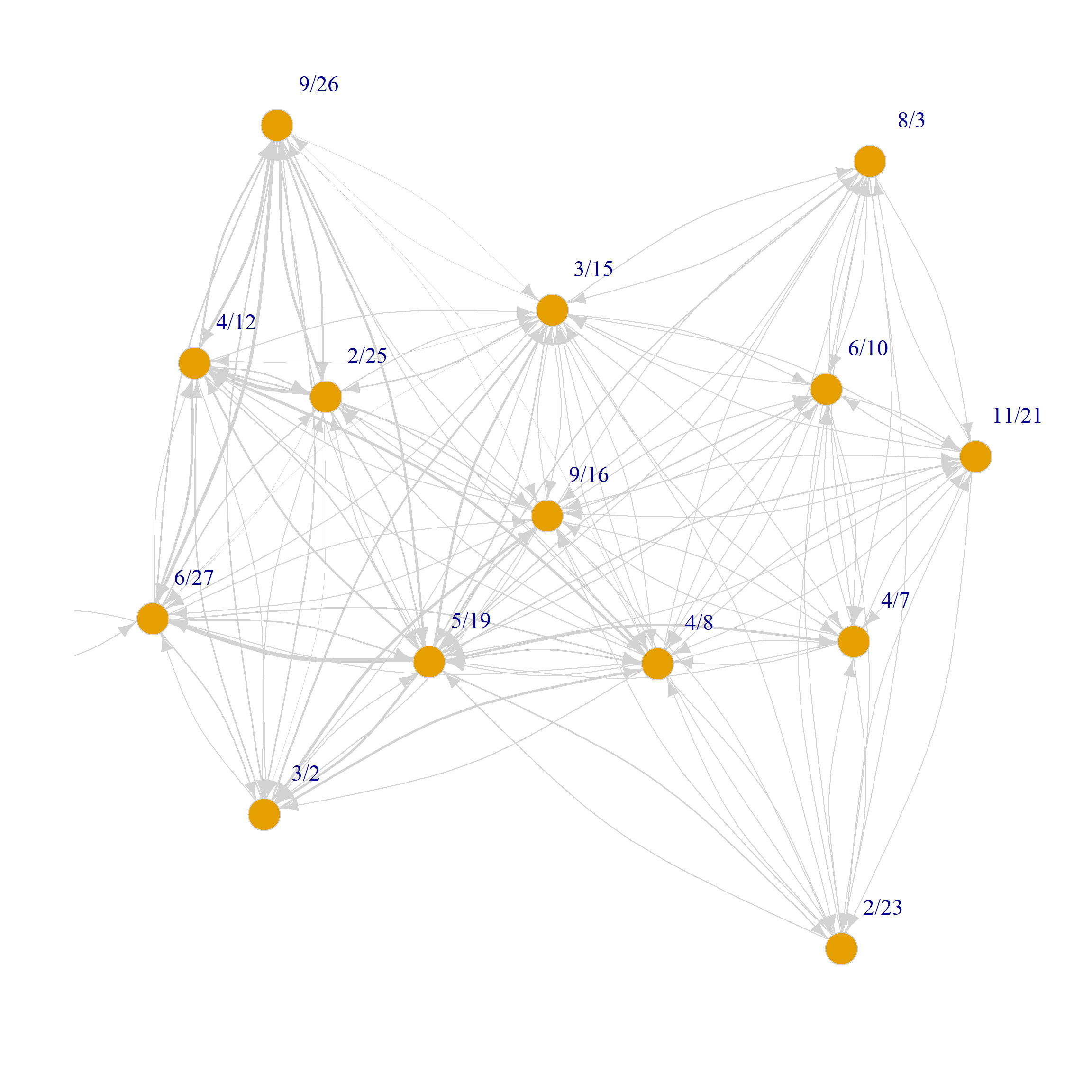

As we just saw projecting the original biadjacency matrix using Breiger’s (1974) approach results in two weighted one mode networks. Because there is an edge between two persons (groups) if they share at least one group (person) the resulting graphs tend to be dense featuring high levels of connectivity between nodes as with Figure 1. This can make it hard to discern the connectivity structure of the projected networks and detect patterns.

One approach to simplifying the visual projections of two-mode networks is to calculate the resulting weighted graph’s minimum spanning tree. For any weighted network, the minimum spanning tree is the graph that connects all nodes using the smallest number of edges that form a tree1, which happens to be \(N-1\) where \(N\) is the number of nodes.

To do this, we can follow Kruskal’s Algorithm. It goes like this:

- First, we create an edgelist containing each of the edge weights of the one-mode projection graph.

- Then we sort the edgelist by weight in increasing order (smallest weights first).

- Then, we create an undirected empty graph with \(N\) nodes.

- Now, we go down the edgelist adding edges to the empty graph one at a time, at each step checking that:

- We are not connecting nodes that have already been connected (avoiding multiedges).

- Additional edges do not create cycles (as the resulting graph would be no longer a tree).

We stop when we have the desired number of edges (\(N-1\)), meaning all nodes are connected in the tree.

Here’s a function that does all of this, taking the weighted projection igraph object as input and returning the minimum spanning tree:

make.mst <- function(x) {

E <- data.frame(as_edgelist(x), w = E(x)$weight) #creating weighted edge list

E <- E[order(E$w), ] #ordering by edge weight

Tr <- make_empty_graph(n = vcount(x), directed = FALSE) #creating empty graph

V(Tr)$name <- V(x)$name

k <- 1

n.e <- ecount(Tr)

n.v <- vcount(Tr) - 1

while(n.e < n.v) {

i <- which(V(x)$name == E[k,1])

j <- which(V(x)$name == E[k,2])

if (are_adjacent(Tr, i, j) == 0) { #checking nodes are not adjacent

Tr <- add_edges(Tr, c(i,j)) #add edge

n.e <- ecount(Tr) #new edge id

if (is_acyclic(Tr) == 0) { #checking new edge does not add a cycle

Tr <- delete_edges(Tr, n.e) # delete edge if it adds a cycle

}

}

n.e <- ecount(Tr)

k <- k + 1

}

return(Tr)

}We can now build the minimum spanning tree graph for each weighted projection:

And here’s a point and line plot the minimum spanning tree for persons and groups in the Southern Women data (we use the layout_as_tree option in igraph):

set.seed(123)

plot(Tr.p,

vertex.size=8, vertex.frame.color="lightgray",

vertex.label.dist=2, layout=layout_as_tree,

vertex.label.cex = 1.5, edge.color = "lightgray",

edge.width = 3, vertex.color = cluster_leading_eigen(Tr.p)$membership)

set.seed(123)

plot(Tr.g,

vertex.size=8, vertex.frame.color="lightgray",

vertex.label.dist=2, layout=layout_as_tree,

vertex.label.cex = 1.5, edge.color = "lightgray",

edge.width = 3, vertex.color = cluster_leading_eigen(Tr.g)$membership)

An Asymmetric Approach to Dual Projection

Zhou et al. (2007) describe an asymmetric approach to projecting a two-mode network into two one-mode weighted networks. The motivation is to move beyond two limitations of the Breiger projection approach: (1) the fact that the standard projection always results in a symmetric weighted adjacency matrix, and (2) the fact that nodes in two-mode networks that only connect to single entity in the other node are necessarily excluded from the traditional projection (they are isolates).

To deal with this issue, Zhou et al. (2007) propose to weigh the one mode projections reciprocally by the degree of the nodes in each mode, similar to the degree-weighting that motivates the CA approach to analyzing two-mode networks we considered here. So the idea is that instead of using the usual Breiger projection we considered above, we instead use the degree-normalized projection.

Recall from that lecture that the degree-normalized projections for persons and groups are obtained as follows:

D.p <- diag(1/rowSums(A)) #inverse of degree matrix of persons

P.pg <- D.p %*% A

rownames(P.pg) <- rownames(A)

D.g <- diag(1/colSums(A)) #inverse of degree matrix of groups

P.gp <- D.g %*% t(A) #person-degree normalized biadjacency matrix

rownames(P.gp) <- colnames(A) #group-degree normalized biadjacency matrix

P.pp <- P.pg %*% P.gp #degree-normalized projection for people

P.gg <- P.gp %*% P.pg #degree-normalized projection for groupsChecking the first rows and columns of the degree-weighted person projection reveals:

Evelyn Laura Theresa Brenda Charlotte

Evelyn 0.186 0.144 0.144 0.134 0.068

Laura 0.165 0.179 0.132 0.132 0.056

Theresa 0.144 0.115 0.157 0.105 0.080

Brenda 0.153 0.132 0.120 0.167 0.092

Charlotte 0.135 0.098 0.160 0.160 0.160Note that the entries of this matrix are not symmetric, like in the standard Breiger projection. For instance the weight of the link going form Evelyn to Laura is 0.144, but the weight of the link going from Laura to Evenly is 0.165.

We can check this formally using the base R function isSymmetric:

Which returns TRUE for the usual Breiger projection but FALSE for the degree-weighted projection.

We can create weighted directed igraph objects from the degree-weighted projections using the function graph_from_adjacency_matrix as follows:

Note that we specify the mode argument to be directed and the weighted argument to be TRUE.

We can of course plot the directed weighted graphs on each mode as usual:

set.seed(123)

plot(G.dp,

vertex.size=8, vertex.frame.color="lightgray",

vertex.label.dist=2, edge.curved=0.2,

vertex.label.cex = 1.5, edge.color = "lightgray",

edge.width = E(G.p)$weight*0.5)

set.seed(123)

plot(G.dg,

vertex.size=8, vertex.frame.color="lightgray",

vertex.label.dist=2, edge.curved=0.2,

vertex.label.cex = 1.5, edge.color = "lightgray",

edge.width = E(G.g)$weight*0.5)

References

Footnotes

Recall that a tree is a connected graph without any cycles.↩︎