8 Nodes and their Neighborhoods

8.1 Node Neighborhoods

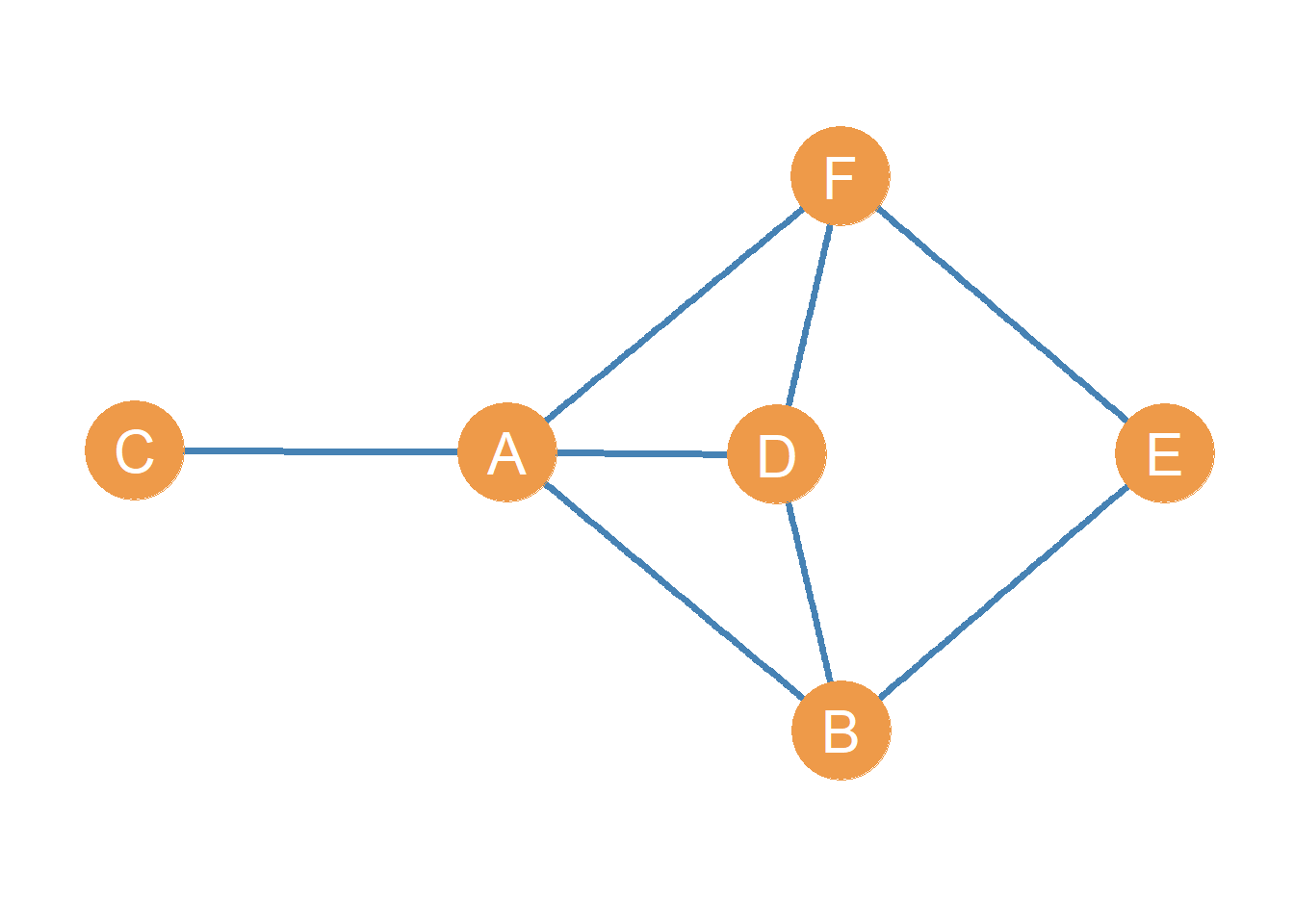

As we have seen, each node in a graph or order \(N\), given by the set \(V = \{v_1, v_2, v_3, \dots v_N\}\) may be adjacent to a certain set of other nodes. In graph theory, these are called the node’s neighbors.The neighborhood of a node in a graph is written as \(\mathcal{N}(v)\), where \(v\) is the node’s name in the graph. For instance, if we are referring to the neighbors of node A in the graph shown as Figure 8.1 we would write \(\mathcal{N}(A)\).

The neighborhood of each node is a proper subset of the larger set of nodes in the graph \(V\). This is written as \(\forall v: \mathcal{N}(v) \subset V\), which translates from math to English as “for all nodes \(v\), the neighborhood of \(v\) is a subset of the larger node set \(V\).” In Figure 8.1 for instance, \(\mathcal{N}(A) = \{B, C, D, F\}\), and \(\mathcal{N}(A) \subset V\).1

8.1.1 Node Neighborhood Intersection

Note that the neighbor sets of two nodes can have members in common. For instance, in Figure 8.1 we have \(\mathcal{N}(A) = \{B, C, D, F\}\) and we also have \(\mathcal{N}(D) = \{A, B, F\}\). These two sets share common members!

Sometimes we may be interested in the total number of other people that two nodes share a connection with. Like when you wonder how many people you and your friend are both friends with (or a social media algorithm lets you know). This is called the intersection of the two node neighborhood sets.

So if A and D are both nodes in a graph, the intersection of their neighborhood sets gives us a list of the other nodes in the graph they are both connected to. Using set theory notation, this can be written as: \(\mathcal{N}(A) \cap \mathcal{N}(D) = \{B, F\}\), which says that nodes A and D have B and F as common neighbors.2

The cardinality of the sets formed by the intersection of the neighborhoods of all the nodes in the graph gives us the number of common neighbors between each pair of nodes, which may be zero if two neighborhoods sets are disjoint. As we saw in Chapter 3, in set theory, the cardinality of a set is the number of members in that set. Thus, the cardinality of the set \(\{A, B, C, D\}\) is four. Two sets are disjoint if they have no members in common, which means that their intersection is the empty set. We will see in a later lesson that this quantity has applications for deriving important matrices from graphs and computing some key network metrics in the network.

Note that two nodes can have common neighbors even if they are not directly connected in the network! So the number of common neighbors is defined for both connected and null dyads.

For instance, in Figure 8.1, the intersection of the neighborhoods of nodes D and E exists and it is given by \(\mathcal{N}(D) \cap \mathcal{N}(E) = \{B, F\}\) even though nodes D and E are not linked (they are nonadjacent).

8.1.2 Node Neighborhood Union

Sometimes we may be interested in the total number of other people that two nodes are connected to, regardless of whether both of them are connected to them. Think of this as adding the set of people that you know with the set of people one of your friends knows, counting the people that your friend knows but you don’t, and the people you know but your friend doesn’t. This is called the union of the two node neighborhood sets.

So if A and D are both nodes in a graph, the union of their neighborhood sets gives us a list of the total number of other nodes in the graph either one is connected to.

Using set theory notation, this can be written as:3

\[ \mathcal{N}(A) \cup \mathcal{N}(D) = \{B, C, F\} \tag{8.1}\]

Which says that nodes A and D have B C, and F as neighbors, but not necessarily common neighbors.

As we will see later, the intersection and union of the neighborhood sets can be used as a basis to construct measures of (structural) similarity between nodes in a graph.

8.2 Node Neighborhoods in Directed Graphs

Just like in undirected (simple) graphs, each node in a directed graph has a node neighborhood. However, because now each node can be the source or destination for a asymmetric edges, this means that we have to differentiate the neighborhood of a node depending on whether the node is the sender or the recipient of a given link.

So, we say that a node j is an an in-neighbor of a node i if there is a directed link with j as the source and i as the destination node. For instance, in Figure 6.2, E is an in-neighbor of C, because there’s a asymmetric edge with E as the source and C as the destination.

In the same way, we say that a node i is an out-neighbor of a node j if there is a directed link with i as the source and j as the destination. For instance, in Figure 6.2, F is an in-neighbor of G, because there’s a asymmetric edge with G as the source and F as the destination

For each node, the full set of in-neighbors forms the in-neighborhood of that node. This is written \(N^{in}(v)\), where \(v\) is the label corresponding to the node. For instance, in Figure 6.2, the node set \(N^{in}(D) = \{B, E, G\}\) is the in-neighborhood of node D.

In the same way, the full set of in-neighbors defines the out-neighborhood of that node. This is written \(N^{out}(v)\), where \(v\) is the label corresponding to the node. For instance, in Figure 6.2, the node set \(N^{out}(B) = \{A, C, D\}\) is the out-neighborhood of node B.

Note that typically, the set of in-neighbors and out-neighbors of a given node will not be exactly the same, and sometimes the two sets will be completely disjoint (they won’t share any members).

Nodes will only show up in both the in and out-neighborhood set when there are reciprocal or mutual ties between the nodes. For instance, in Figure 6.2, the out-neighborhood of node F is \(\{A\}\) and the in-neighborhood is \(\{A, G\}\). Here node A shows up in both the in and out-neighborhood sets because A has a reciprocal tie with F.