Social Networks

What are social networks? As you saw in the tree chart shown in Figure 1.2 in the previous lesson, only a subset of networks in the world as social networks. The key difference between social networks and other networks is that social networks have to involve people (or groups of people) and their perceptions, thoughts, interactions, and behaviors.

Sometimes interactions between people are mediated by technologies. For instance, people can connect to one another by texting on their phone or traveling by plane, in which case the differentiation between what is a technological and a social network becomes a matter of degree.

In this class we will deal with networks that are closer to the “purely social” end of the scale: Those involving people, their perceptions, interactions, sentiments, exchanges, memberships, and relations. The primary perspective that we will take is that of social network analysis as developed in the discipline of sociology since the 1970s.

As noted, the inter-disciplinary field in charge of studying social networks is called social network analysis (SNA), and is composed of insights from a variety of other social science disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, communication, and others (see Figure 2.1). SNA in its turn, is part of an even larger interdisciplinary field in charge of studying all types of networks called network science which includes work in physics, computer science, data science, biology, engineering, mathematics, and other fields. The relationship between these different scientific fields is depicted in Figure 2.2.

The Two Faces of Social Network Analysis

Social network analysis has two broad aspects. One, generally referred to as network theory is about figuring out how networks work and what networks do to and for people. In essence, social network theories are general statements about how people behave in networks and how networks themselves “behave”“; that is where network relations come from, what they do, and what consequences they have for the people involved.

For instance, the idea of social capital that is, that the connections that you have to others can bring you certain types of benefits, is part of network theory. In fact, as we will see later, a good chunk of network theory (but not all!), such as the theory of structural holes, or the strength of weak ties theory, can be thought of as theories of social capital (Borgatti and Halgin 2011). Other types of network theory deal with how networks of sentiment relations (e.g. likes and dislikes) form, while other tell us about how things flow through networks.

Another branch of social network analysis deals with how to measure various network properties. This branch of social network analysis, called network measurement links social network concepts to some type of mathematical or quantitative representation. Since this branch of network analysis deals with measurement, it is where mathematics and other forms of quantitative representation of networks (such as matrices) come in handy.

If math scares you, don’t worry. Our job is to walk you slowly through it. But you still may be asking: Why math though? The beauty of math, is that it allows us to take some fuzzy social science concepts, stated in natural language, such as the idea of “popularity” or “social position” or “strength of connection” and give it a precise representation. That way we can use networks to learn about what makes the social world go round or predict why some people, organizations, or even whole countries are successful and others are not (among other things).

The two “faces” of SNA (network theory and network measurement) as well as some choice examples are depicted in Figure 2.3. Don’t get nervous if you do not know what the things at the bottom of the diagram (e.g., “density”), mean. We will explain them to you in the forthcoming lessons.

We can develop theories or measure network properties at multiple levels of analysis. Like other complex systems, social networks feature dynamics at multiple nested levels. We will deal with five such levels in what follows.

At the node level we may be interested in what properties nodes have by virtue of the connections they have within the network. Both the idea of an ego network and various measures of social position based on centrality are defined at this level.

At the dyad and triad levels, we may be interested in the properties that the edges or the links have by virtue of settling into certain configurations. Both the idea of tie strength and various theories dealing with triples of nodes such as Balance Theory (Davis 1963), Strength of Weak Ties Theory (Granovetter 1973), the theory of Structural Holes (Burt 1995), and Simmmelian Tie Theory (Krackhardt 1999) are defined this level.

At the level of motifs may be interested in the network substructures or the “lego building blocks” that make up the larger network. For instance, how many configurations of three, four, or five actors can we observe?

At the subgroup or community We may be interested in properties that subsets or clusters or nodes have by virtue of the set of connections they share. Here, theories and measures of group cohesion, and community structure in networks have been developed.

Finally, we may be interested in measuring properties and theorizing the structure and dynamics of the whole network. This may includes quantities that are sums or averages of features computed at lower levels, or they may include properties applicable to the system as a whole (e.g., whether it would take a short or a long time to get something from one randomly selected person in the network to another). Ideas of whether human networks constitute Small Worlds (Milgram 1967) are defined at this level.

In Figure 2.4 we can see how the nested structure of social networks can be depicted. At all levels we can develop specific theories to understand what is happening at that slice or develop special measures designed to link the concepts of those theories to a precise quantitative representation.

Networks, Graphs, and Matrices

’Social network analysis is an influential, and now increasingly widespread, methodological approach for analyzing the social world. Traditionally, sociologists have studied relationships using a variety of observational strategies, both qualitative, such as ethnography and interviews, and quantitative, such as those based on the social survey. However, beginning in earnest in the 1950s, sociologists began to make concerted use of mathematical techniques from a branch of pure mathematics called graph theory and a branch of applied mathematics called matrix algebra to develop scientific models of social relationships and to come up with measures connecting key concepts from social theory, such as roles, prominence, and prestige, to tangible empirical evidence.

Social Network Analysis (SNA) is the use of graph-theoretic and matrix algebraic techniques to study social structure and social relationships, which exist in real world networks. While much of this activity has to do with the measurement of social network concepts, Social Network Theory is the branch of social networks that tells us what social networks are, what they do, how they make a difference (negative or positive) in the world, and where networks come from and how they change over time.

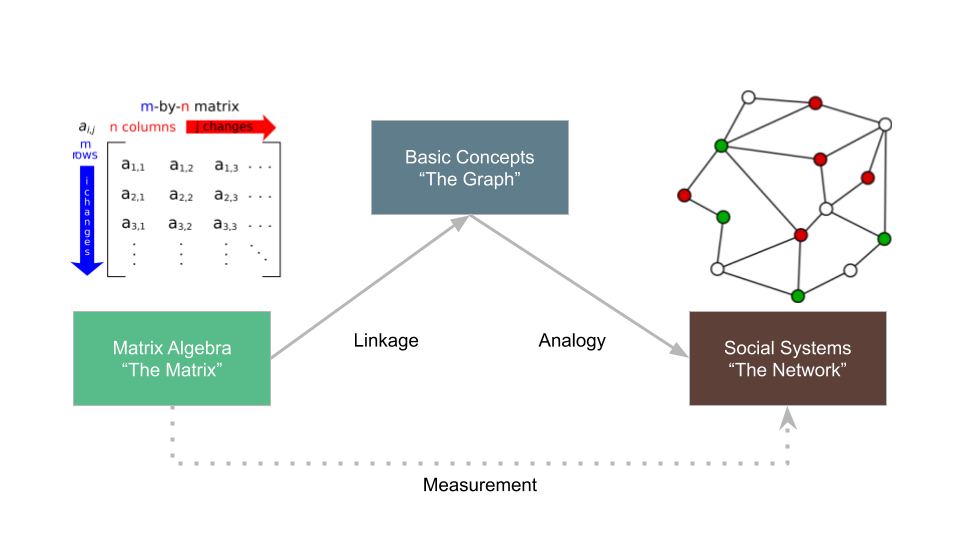

A key skill you will gain by taking this class is to transition swiftly from these three ways of talking about networks, namely, networks as real world systems of social interactions, networks as represented mathematically as graphs, and networks represented quantitatively as matrices. This three-step transition is represented in Figure 2.5. Another skill you will gain by taking this class is how to apply social network theory to understand how real world networks work and change.

References

Borgatti, Stephen P, and Daniel S Halgin. 2011. “On Network Theory.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1168–81.

Burt, Ronald S. 1995. Structural Holes. Harvard University Press.

Davis, James A. 1963. “Structural Balance, Mechanical Solidarity, and Interpersonal Relations.” American Journal of Sociology 68 (4): 444–62.

Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–80.

Krackhardt, David. 1999. “The Ties That Torture: Simmelian Tie Analysis in Organizations.” Research in the Sociology of Organizations 16 (1): 183–210.

Milgram, Stanley. 1967. “The Small World Problem.” Psychology Today 2 (1): 60–67.

2.1 Social Networks

What are social networks? As you saw in the tree chart shown in Figure 1.2 in the previous lesson, only a subset of networks in the world as social networks. The key difference between social networks and other networks is that social networks have to involve people (or groups of people) and their perceptions, thoughts, interactions, and behaviors.

Sometimes interactions between people are mediated by technologies. For instance, people can connect to one another by texting on their phone or traveling by plane, in which case the differentiation between what is a technological and a social network becomes a matter of degree.

In this class we will deal with networks that are closer to the “purely social” end of the scale: Those involving people, their perceptions, interactions, sentiments, exchanges, memberships, and relations. The primary perspective that we will take is that of social network analysis as developed in the discipline of sociology since the 1970s.

As noted, the inter-disciplinary field in charge of studying social networks is called social network analysis (SNA), and is composed of insights from a variety of other social science disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, communication, and others (see Figure 2.1). SNA in its turn, is part of an even larger interdisciplinary field in charge of studying all types of networks called network science which includes work in physics, computer science, data science, biology, engineering, mathematics, and other fields. The relationship between these different scientific fields is depicted in Figure 2.2.