Basic Network Statistics

Loading Data

Here we will analyze a small network and computer some basic statistics of interest. The first thing we need to do is get some data! For this purpose, we will use the package networkdata (available here). To install the package, use the following code:

To load the network datasets in the networkdata just type:

The package contains a bunch of human and animal social networks to browse through them, type:

We will pick one of the movies for this analysis, namely, Pulp Fiction. This is movie_559. In the movie network two characters are linked by an edge if they appear in a scene together. The networkdata data sets come in igraph format, so we need to load that package (or install it using install.packages if you haven’t done that yet).

Number of Nodes and Edges

Now we are ready to compute some basic network statistics. As with any network, we want to know what the number of nodes and the number of edges (links) are. Since this is a relatively small network, we can begin by listing the actors.

+ 38/38 vertices, named, from 9e7cc7a:

[1] BRETT BUDDY BUTCH CAPT KOONS

[5] ED SULLIVAN ENGLISH DAVE ESMARELDA FABIENNE

[9] FOURTH MAN GAWKER #2 HONEY BUNNY JIMMIE

[13] JODY JULES LANCE MANAGER

[17] MARSELLUS MARVIN MAYNARD MIA

[21] MOTHER PATRON PEDESTRIAN PREACHER

[25] PUMPKIN RAQUEL ROGER SPORTSCASTER #1

[29] SPORTSCASTER #2 THE GIMP THE WOLF VINCENT

[33] WAITRESS WINSTON WOMAN YOUNG MAN

[37] YOUNG WOMAN ZED The function V takes the igraph network object as input and returns an igraph.vs object as output (short for “igraph vertex sequence”), listing the names (if given as a graph attribute) of each node. The first line also tells us that there are 38 nodes in this network.

The igraph.vs object operates much like an R character vector, so we can query its length to figure out the number of nodes:

The analogue function for edges in igraph is E which also takes the network object as input and returns an object of class igraph.es (“igraph edge sequence”) as output:

+ 102/102 edges from 9e7cc7a (vertex names):

[1] BRETT --MARSELLUS BRETT --MARVIN

[3] BRETT --ROGER BRETT --VINCENT

[5] BUDDY --MIA BUDDY --VINCENT

[7] BRETT --BUTCH BUTCH --CAPT KOONS

[9] BUTCH --ESMARELDA BUTCH --GAWKER #2

[11] BUTCH --JULES BUTCH --MARSELLUS

[13] BUTCH --PEDESTRIAN BUTCH --SPORTSCASTER #1

[15] BUTCH --ENGLISH DAVE BRETT --FABIENNE

[17] BUTCH --FABIENNE FABIENNE --JULES

[19] FOURTH MAN --JULES FOURTH MAN --VINCENT

+ ... omitted several edgesThis tells us that there are 102 edges (connected dyads) in the network. Some of these include Brett and Marsellus and Fabienne and Jules, but not all can be listed for reasons of space.

igraph also has two dedicated functions that return the number of nodes and edges in the graph in one fell swoop. They are called vcount and ecount and take the graph object as input:

Graph Density

Once we have the number of edges and nodes, we can calculate the most basic derived statistic in a network, which is the density. Since the movie network is an undirected graph, the density is given by:

\[ \frac{2m}{n(n-1)} \]

Where \(m\) is the number of edges and \(n\) is the number of nodes, or in our case:

Of course, igraph has a dedicated function called edge_density to compute the density too, which takes the igraph object as input:

Degree

The next set of graph metrics are based on the degree of the graph. We can list the graph’s degree set using the igraph function degree:

BRETT BUDDY BUTCH CAPT KOONS ED SULLIVAN

7 2 17 5 2

ENGLISH DAVE ESMARELDA FABIENNE FOURTH MAN GAWKER #2

4 1 3 2 3

HONEY BUNNY JIMMIE JODY JULES LANCE

8 3 4 16 4

MANAGER MARSELLUS MARVIN MAYNARD MIA

5 10 6 3 11

MOTHER PATRON PEDESTRIAN PREACHER PUMPKIN

5 5 3 3 8

RAQUEL ROGER SPORTSCASTER #1 SPORTSCASTER #2 THE GIMP

3 6 2 1 2

THE WOLF VINCENT WAITRESS WINSTON WOMAN

3 25 4 3 5

YOUNG MAN YOUNG WOMAN ZED

4 4 2 The degree function takes the igraph network object as input and returns a plain old R named vector as output with the names being the names attribute of vertices in the network object.

Usually we are interested in who are the “top nodes” in the network by degree (a kind of centrality). To figure that out, all we need to do is sort the degree set (to generate the graph’s degree sequence) and list the top entries:

VINCENT BUTCH JULES MIA MARSELLUS HONEY BUNNY

25 17 16 11 10 8

PUMPKIN BRETT

8 7 Line 1 stores the degrees in an object “d”, line 2 creates a “sorted” version of the same object (from bigger to smaller) and line 3 shows the first eight entries of the sorted degree sequence.

Because the degree vector “d” is just a regular old vector we can use native R mathematical operations to figure out things like the sum, maximum, minimum, and average degree of the graph:

So the sum of degrees is 204, the maximum degree is 25 (belonging to Vincent), the minimum is one, and the average is about 5.4.

Note that these numbers recreate some well-known equalities in graph theory:

- The sum of degrees is twice the number of edges (the first theorem of graph theory):

- The average degree is just the sum of degrees divided by the number of nodes:

- The density is just the average degree divided by the number of nodes minus one, as explained here:

Some people also consider the degree variance of the graph as a measure of inequality of connectivity in the system. It is equal to the average sum of square deviations of each node’s degree from the average:

\[ \mathcal{v}(G) = \frac{\sum_i (k_i - \bar{k})^2}{n} \]

This tells us that there is a lot of inequality in the distribution of degrees in the graph (a graph with all nodes equal degree would have variance zero).

The Degree Distribution in Undirected Graphs

Another way of looking at inequalities of degrees in a graph is to examine its degree distribution. This gives us the probability of observing a node with a given degree k in the graph.

[1] 0.000 0.053 0.158 0.237 0.158 0.132 0.053 0.026 0.053 0.000 0.026 0.026

[13] 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.026 0.026 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

[25] 0.000 0.026The igraph function degree_distribution just returns a numeric vector of the same length as the maximum degree of the graph plus one. In this case that’s a vector of length 25 + 1 = 26. The first entry gives us the proportion of nodes with degree zero (isolates), the second the proportion of nodes of degree one, and so on up to the graph’s maximum degree.

Since there are no isolates in the network, we can ignore the first element of this vector, to get the proportion of nodes of each degree in the Pulp Fiction network. To that, we fist create a two-column data.frame with the degrees in the first column and the proportions in the second:

degree <- c(1:max(d))

prop <- deg.dist

prop <- prop[-1]

deg.dist <- data.frame(degree, prop)

deg.dist degree prop

1 1 0.053

2 2 0.158

3 3 0.237

4 4 0.158

5 5 0.132

6 6 0.053

7 7 0.026

8 8 0.053

9 9 0.000

10 10 0.026

11 11 0.026

12 12 0.000

13 13 0.000

14 14 0.000

15 15 0.000

16 16 0.026

17 17 0.026

18 18 0.000

19 19 0.000

20 20 0.000

21 21 0.000

22 22 0.000

23 23 0.000

24 24 0.000

25 25 0.026Of course, a better way to display the degree distribution of a graph is via some kind of data visualization, particularly for large networks where a long table of numbers is just not feasible. To do that, we can call on our good friend ggplot:

# install.packages(ggplot2)

library(ggplot2)

p <- ggplot(data = deg.dist, aes(x = degree, y = prop))

p <- p + geom_bar(stat = "identity", fill = "red", color = "red")

p <- p + theme_minimal()

p <- p + labs(x = "", y = "Proportion",

title = "Degree Distribution in Pulp Fiction Network")

p <- p + geom_vline(xintercept = mean(d),

linetype = 2, linewidth = 0.5, color = "blue")

p <- p + scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25))

p

The plot clearly shows that the Pulp Fiction network degree distribution is skewed with a small number of characters having a large degree \(k \geq 15\) while most other characters in the movie have a small degree \(k \leq 5\) indicating inequality of connectivity in the system.

The Degree Correlation

Another overall network statistic we may want to know is the degree correlation (Newman 2002). How do we compute it? Imagine taking each edge in the network and creating two degree vectors, one based on the degree of the node in one end and the degre of the node in another. Then the degree assortativity coefficient is just the Pearson product moment correlation between these two vectors.

Let’s see how this would work for the Pulp Fiction network. First we need to extract an edge list from the graph:

[,1] [,2]

[1,] "BRETT" "MARSELLUS"

[2,] "BRETT" "MARVIN"

[3,] "BRETT" "ROGER"

[4,] "BRETT" "VINCENT"

[5,] "BUDDY" "MIA"

[6,] "BUDDY" "VINCENT" We can see that the as_edgelist function takes the igraph network object as input and returns an \(E \times 2\) matrix, with \(E = 102\) being the number of rows. Each column of the matrix records the name of the node on each end of the edge. So the first row of the edge list with entries “BRETT” and “MARSELLUS” tells us that there is an edge linking Brett and Marsellus, and so forth for each row.

To compute the correlation between the degrees of each node, all we need to do is attach the corresponding degrees to each name for each of the columns of the edge list, which can be done via data wrangling magic from the dplyr package (part of the tidyverse):

# install.packages(dplyr)

library(dplyr)

deg.dat <- data.frame(name1 = names(d), name2 = names(d), d)

el.temp <- data.frame(name2 = g.el[, 2]) %>%

left_join(deg.dat, by = "name2") %>%

dplyr::select(c("name2", "d")) %>%

rename(d2 = d)

d.el <- data.frame(name1 = g.el[, 1]) %>%

left_join(deg.dat, by = "name1") %>%

dplyr::select(c("name1", "d")) %>%

rename(d1 = d) %>%

cbind(el.temp)

head(d.el) name1 d1 name2 d2

1 BRETT 7 MARSELLUS 10

2 BRETT 7 MARVIN 6

3 BRETT 7 ROGER 6

4 BRETT 7 VINCENT 25

5 BUDDY 2 MIA 11

6 BUDDY 2 VINCENT 25Line 3 creates a two-column data frame called “deg.dat” with as many rows as there are nodes in the network. The first two columns contain the names of each node (identically listed with different names) and the third columns contains the corresponding node’s degree.

Lines 4-7 use dplyr functions to create a new object “el.temp” joining the degree information to each of the node names listed in the second position in the original edge list “g.el,” and rename the imported column of degrees “d2.”

Lines 8-12 do the same for the nodes listed in the first position in the original edge list, renames the imported columns of degrees “d1,” and the binds the columns of the “el.temp” object to the new object “d.el.” The resulting object has four columns: Two for the names of the nodes incident to each edge on the edge list (columns 1 and 3), and two other ones corresponding to the degrees of the corresponding nodes (columns 2 and 4).

We can see from the output of the first few rows of the “d.el” object that indeed “BRETT” is assigned a degree of 7 in each row of the edge list, “BUDDY” a degree of 2, “MARSELLUS” a degree of 10, “VINCENT” a degree of 25 and so forth.

Now to compute the degree correlation in the network all we need to do is call the native R function cor on the two columns from “d.el” that containing the degree information. Note that because each degree appears twice at the end of each edge in an undirected graph (as both “sender” and “receiver”), we need to double each column by appending the other degree column at the end. So the first degree column is the vector:

And the second degree column is the vector:

And the graph’s degree correlation (Newman 2003) is just the Pearson correlation between these two degree vectors:

The result \(r_{deg} = -0.29\) tells us that there is anti-correlation by degree in the Pulp Fiction network. That is high-degree characters tend to appear with low degree characters, or conversely, high-degree characters (like Marsellus and Jules) don’t appear together very often.

Of course, igraph has a function called assortativity_degree that does all the work for us:

Interlude: Loading Network Data from a File

When get network data from an archival source, and it will be in the form of a matrix or an edge list, typically in some kind of comma separated value (csv) format. Here will show how to input that into R to create an igraph network object from an outside file.

First we will write the Pulp Fiction data into an edge list and save it to disk. We already did that earlier with the “g.el” object. So all we have to do is save it to your local folder as a csv file:

The write.csv function just saves an R object into a .csv file. Here the R object is “g.el” and we asked it to save just the columns which contain the name of each character. This represents the adjacency relations in the network as an edge list. We use the package here to keep track of our working directory. See here (pun intended) for details.

Now suppose that’s the network we want to work with and it’s saved in our hard drive. To load it, we just type:

name1 name2

1 BRETT MARSELLUS

2 BRETT MARVIN

3 BRETT ROGER

4 BRETT VINCENT

5 BUDDY MIA

6 BUDDY VINCENTWhich gives us the edge list we want now saved into an R object of class data.frame. So all we need is to convert that into an igraph object. To do that we use one of the many graph_from... functions in the igraph package. In this case, we want graph_from_edgelist because our network is stored as an edge list:

+ 38/38 vertices, named, from ff1e988:

[1] BRETT MARSELLUS MARVIN ROGER

[5] VINCENT BUDDY MIA BUTCH

[9] CAPT KOONS ESMARELDA GAWKER #2 JULES

[13] PEDESTRIAN SPORTSCASTER #1 ENGLISH DAVE FABIENNE

[17] FOURTH MAN HONEY BUNNY MANAGER JIMMIE

[21] JODY PATRON PUMPKIN RAQUEL

[25] WINSTON LANCE MAYNARD THE GIMP

[29] ZED ED SULLIVAN MOTHER WOMAN

[33] PREACHER SPORTSCASTER #2 THE WOLF WAITRESS

[37] YOUNG MAN YOUNG WOMAN + 102/102 edges from ff1e988 (vertex names):

[1] BRETT --MARSELLUS BRETT --MARVIN

[3] BRETT --ROGER BRETT --VINCENT

[5] BUDDY --MIA VINCENT --BUDDY

[7] BRETT --BUTCH BUTCH --CAPT KOONS

[9] BUTCH --ESMARELDA BUTCH --GAWKER #2

[11] BUTCH --JULES MARSELLUS --BUTCH

[13] BUTCH --PEDESTRIAN BUTCH --SPORTSCASTER #1

[15] BUTCH --ENGLISH DAVE BRETT --FABIENNE

[17] BUTCH --FABIENNE JULES --FABIENNE

[19] JULES --FOURTH MAN VINCENT --FOURTH MAN

+ ... omitted several edgesWhich gives us back the original igraph object we have been working with. Note that first we converted the data.frame object into a matrix object. We also specified that the graph is undirected by setting the option directed to false.

The Average Shortest Path Length

The final statistic people use to characterize networks is the average shortest path length. In a network, even non-adjacent nodes, could be indirectly connected to other nodes via a path of some length (\(l > 1\)) So it is useful to know what the average of this quantity is across all dyads in the network.

To do that, we first need to compute the length of the shortest path \(l\) for each pair of nodes in the network (also known as the geodesic distance). Adjacent nodes get an automatic score of \(l = 1\). In igraph this is done as follows:

BRETT MARSELLUS MARVIN ROGER VINCENT BUDDY MIA

BRETT 0 1 1 1 1 2 2

MARSELLUS 1 0 1 1 1 2 1

MARVIN 1 1 0 1 1 2 2

ROGER 1 1 1 0 1 2 2

VINCENT 1 1 1 1 0 1 1

BUDDY 2 2 2 2 1 0 1

MIA 2 1 2 2 1 1 0The igraph function distances takes the network object as input and returns the desired shortest path matrix. So for instance, Brett is directly connected to Butch (they appear in a scene together) but indirectly connected to Buddy via a path of length two (they both appear in scenes with common neighbors even if they don’t appear together).

The maximum distance between two nodes in the graph (the longest shortest path to put it confusingly) is called the graph diameter. We can find this out simply by using the native R function for the maximum on the shortest paths matrix:

This means that in the Pulp Fiction network the maximum degree of separation between two characters is a path of length 8.

Of course, we cann also call the igraph function diammeter:

Once we have the geodesic distance matrix, it is easy to calculate the average path length of the graph:

First (line 1) we sum all the rows (or columns) of the geodesic distance matrix. This vector (of the same length as the number of nodes) gives us the sum of the geodesic distance of each node to each of the nodes (we will use this to compute closeness centrality later).

Then (line 2) we divide this vector by the number of nodes minus one (to exclude the focal node) to create a vector of the average distance of each node to each of the other nodes.

Finally (line 3) we take the average across all nodes of this average distance vector to get the graph’s average shortest path length, which in this case equals L = 2.3.

This means that, on average, each character in Pulp Fiction is separated by little less than three contacts in the co-appearance network (a fairly small world).

Of course this can also be done in just one step on igraph:

Putting it all Together

Now we can put together all the basic network statistics that we have computed into some sort of summary table, like the ones here. We first create a vector with the names of each statistic:

Then we create a vector with the values:

We can then put these two vector together into a data frame:

We can then use the package kableExtra (a nice table maker) to create a nice html table:

# intall.packages(kableExtra)

library(kableExtra)

kbl(net.stats, format = "pipe", align = c("l", "c"),

caption = "Key Statistics for Pulp Fiction Network.") %>%

kable_styling(bootstrap_options = c("hover", "condensed", "responsive"))| Stat | Value |

|---|---|

| Nodes | 38.00 |

| Edges | 102.00 |

| Min. Degree | 1.00 |

| Max. Degree | 25.00 |

| Avg. Degree | 5.37 |

| Degree Corr. | -0.29 |

| Diameter | 5.00 |

| Avg. Shortest Path Length | 2.33 |

Graph Degree Metrics in Directed Graphs

As we saw earlier, the degree distribution and the degree correlation are two basic things we want to have a sense of when characterizing a network, and we showed examples for the undirected graph case. However, when you have a network measuring a tie with some meaningful “from” “to” directionality (represented as a directed graph) the number of things you have to compute in terms of degrees “doubles.”

For instance, instead of a single degree set and sequence, now we have two: An outdegree and an indegree set and sequence. The same thing applies to the degree distribution and the degree correlation.

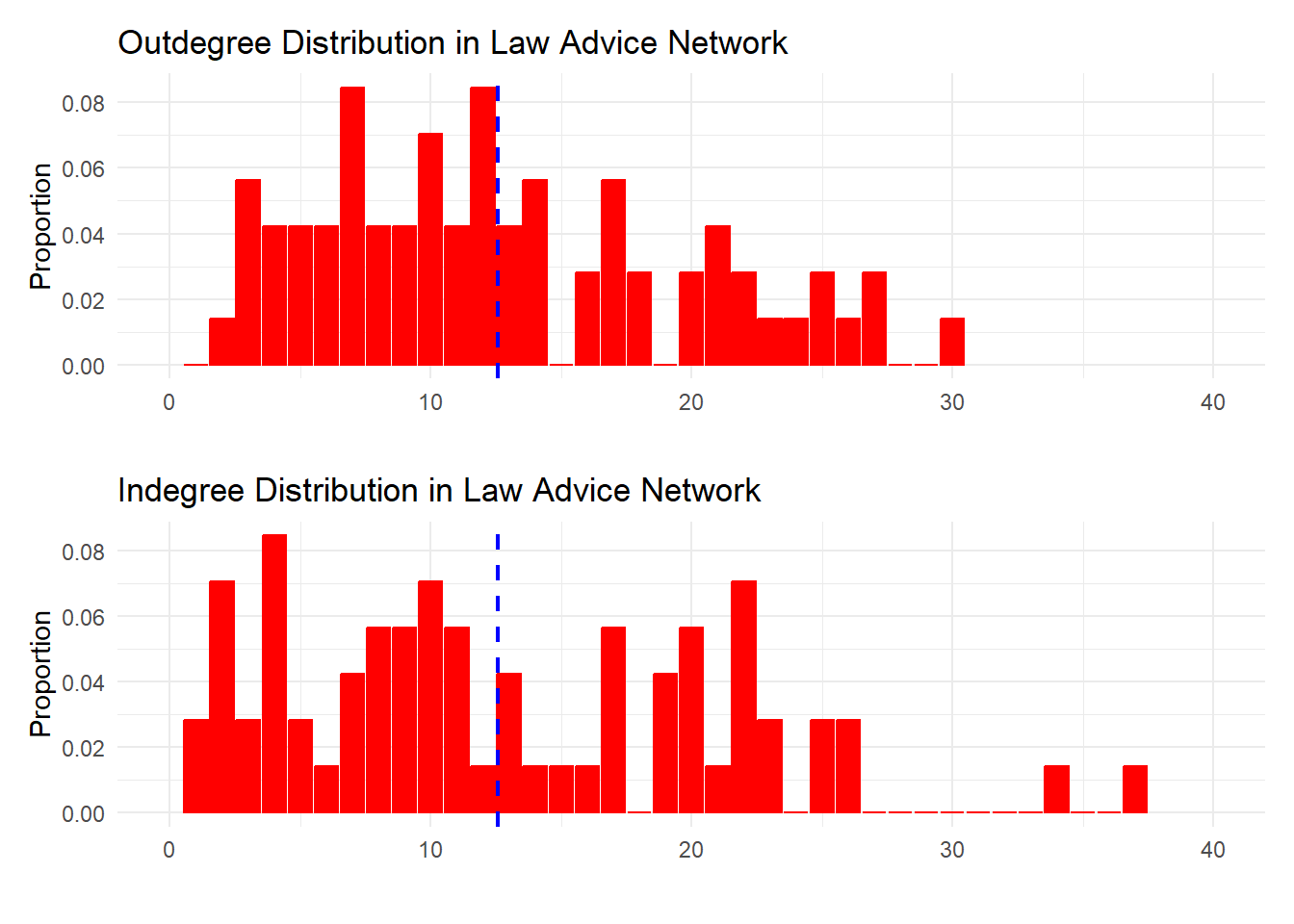

The Indegree and Outdegree Distributions

In the case of the degree distribution, now we have two distributions: An outdegree distribution and an indegree distribution.

Let’s see an example using the law_advice data.

So the main complication is that now we have to specify a value for the “mode” argument; “in” for indegree and “out” for outdegree.

That also means that when plotting, we have to create two data frames and present two plots.

First the data frames:

i.d <- degree(g, mode = "in")

o.d <- degree(g, mode = "out")

i.d.vals <- c(0:max(i.d))

o.d.vals <- c(0:max(o.d))

i.deg.dist <- data.frame(i.d.vals, i.prop)

o.deg.dist <- data.frame(o.d.vals, o.prop)

head(i.deg.dist) i.d.vals i.prop

1 0 0.01408451

2 1 0.02816901

3 2 0.07042254

4 3 0.02816901

5 4 0.08450704

6 5 0.02816901 o.d.vals o.prop

1 0 0.01408451

2 1 0.00000000

3 2 0.01408451

4 3 0.05633803

5 4 0.04225352

6 5 0.04225352Now, to plotting. To be effective, the resulting plot has to show the outdegree and indegree distribution side by side so as to allow the reader to compare. To do that, we first generate each plot separately:

library(ggplot2)

p <- ggplot(data = o.deg.dist, aes(x = o.d.vals, y = o.prop))

p <- p + geom_bar(stat = "identity", fill = "red", color = "red")

p <- p + theme_minimal()

p <- p + labs(x = "", y = "Proportion",

title = "Outdegree Distribution in Law Advice Network")

p <- p + geom_vline(xintercept = mean(o.d),

linetype = 2, linewidth = 0.75, color = "blue")

p1 <- p + scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40)) + xlim(0, 40)

p <- ggplot(data = i.deg.dist, aes(x = i.d.vals, y = i.prop))

p <- p + geom_bar(stat = "identity", fill = "red", color = "red")

p <- p + theme_minimal()

p <- p + labs(x = "", y = "Proportion",

title = "Indegree Distribution in Law Advice Network")

p <- p + geom_vline(xintercept = mean(i.d),

linetype = 2, linewidth = 0.75, color = "blue")

p2 <- p + scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40)) + xlim(0, 40)Then we use the magical package patchwork to combine the plots:

The data clearly shows that while both distributions are skewed, the indegree distribution is more heterogeneous, with a larger proportion of nodes in the high end of receiving advice as compared to giving advice.

Note also that since the mean degree is the same regardless of whether we use the out or indegree distribution, then the blue line pointing to the mean degree falls in the same spot on the x-axis for both plots.

The Four Different Flavors of Degree Correlations in the Directed Case

The same doubling (really quadrupling) happens to degree correlations in directed graphs. While in an undirected graph, there is a single degree correlation, in the directed case we have four quantities to compute: The out-out degree correlation, the in-in degree correlation, the out-in degree correlation, and the in-out degree correlation (see here, p. 38).

To proceed, we need to create an edge list data set with six columns: The node id of the “from” node, the node id of the “to” node, the indegree of the “from” node, the outdegree of the “from” node, the indegree of the “to” node, and the outdegree of the “to” node.

We can adapt the code we used for the undirected case for this purpose. First, we create an edge list data frame using the igraph function as_data_frame:

fr to

1 1 2

2 1 17

3 1 20

4 2 1

5 2 6

6 2 17Note that we have to specify that this is in an igraph function by typing igraph:: in front of the as_data_frame because there is an (older) dplyr function with the same name that was used for data wrangling.

Second, we create data frames containing the in and outdegrees of each node in the network:

Third, we merge this info into the edge list data frame to get the in and outdegrees of the from and to nodes in the directed edge:

d.el <- g.el %>%

left_join(deg.dat.fr) %>%

rename(o.d.fr = o.d, i.d.fr = i.d) %>%

left_join(deg.dat.to, by = "to") %>%

rename(o.d.to = o.d, i.d.to = i.d)

head(d.el) fr to o.d.fr i.d.fr o.d.to i.d.to

1 1 2 3 22 7 23

2 1 17 3 22 21 26

3 1 20 3 22 11 22

4 2 1 7 23 3 22

5 2 6 7 23 0 21

6 2 17 7 23 21 26Now we can compute the four different flavors of the degree correlation for directed graphs:

[1] -0.0054[1] 0.187[1] -0.0283[1] -0.0843These results tell us that there is not much degree assortativity going on in the law advice network, except for a slight tendency of people who receive advice from lots of others to give advice to people who also receive advice from a lot of other people (the “in-in” correlation)

Note that by default, the assortativity_degree function in igraph only returns the out-in correlation for directed graphs:

That is, assortativity_degree checks if more active senders are more likely to send ties to people who are popular receivers of ties.